On the windswept courtyard of Agios Nikolaos monastery, overlooking the sea that separates Spetses from the Peloponnese, artists Leda Papaconstantinou and Lizzie Calligas are sharing with me the story behind the sprawling black-and-white pebble design that covers the entire floor. Their voices float softly atop a deafening choir of cicadas like riding a wave. It is an early August Sunday afternoon, about sunset time.

"This courtyard you see here has been crafted in an amazing way," remembers Leda Papaconstantinou. "The local craftsmen brought the children from the primary school here, and the children worked with them for some time. That's how they all learned the craft. Those children are today in their late fifties. I happen to know one of them. That's how I have this information."

The island of Spetses is known in Greece for many things. It has played a key part in the 1821 uprising against the Ottomans. It has been a favourite haunt for jet setters and politicians from the 1950's to this day. And its close proximity to Athens means that many Athenians own holiday houses here. Spetses is also known for its well-preserved neoclassical architecture and traditional pebble floors, like the one here in front of Agios Nikolaos. These masterfully executed mosaics are made with grey and white pebbles harvested from the beach and set in sand by expert craftsmen. They usually depict marine subjects — anchors, dolphins, ships, stars, waves — as well as abstract patterns. Traditionally, women drafted the designs on paper, then the men executed them.

"The courtyards are exceptional," confirms Lizzie Calligas. "Some of them are masterpieces. There's books about them with photographs." We marvel at the well-proportioned cypress trees, human figures and boats that adorn the courtyard. "Next year this courtyard is to undergo maintenance," says Leda Papaconstantinou. "I hope the children will come again, to learn something that is important and which is part of history."

This care for cultural education and preservation plays an important part in Leda Papaconstantinou's work since the 1970's. It is the same care that has fuelled her extensive archival work on Spetses, as well as her involvement in the programming of the Spetses Ecclesiastical Museum. Leda Papaconstantinou is a member of a board of locals who are bringing a contemporary angle to the tiny island's cultural heritage. They renovated a small room at the monastery of Agios Nikolaos, where the museum is housed, and have been using it as a contemporary art gallery for the past three years. "The only condition," she says, "is that the exhibitions should have some connection to the island. Either the people are related to the island, or the subject somehow [has some connection]. We document everything we do. This way, an archive is created."

Living in archive mode

There is already an archive in the same building, the Spetses Historical Archive, which documents the island's history since the early 1800's. But as Leda Papaconstantinou points out, there has been no documentation of the island's artistic and cultural assets so far. The very first exhibition organised by the new museum was dedicated to a local, self-taught painter. "We thought our first exhibition should be about a true local. That is why we spoke to Nikos Mantas, a folk painter." The exhibition was of historical significance, because it was the nonagenarian artist's first, and was celebrated by the entire community. Lizzie Calligas remembers: "[On the day of the opening] he was here on this very courtyard with his family. He was very moved." "Even the bells were ringing," Leda Papaconstantinou adds. "At some point the priest climbed the bell tower and rang the bells in celebration. This old man [i.e. Mantas] was ninety six years old and he was exhibiting his work for the very first time. He was a friend of mine and of my parents, and even trusted me enough to let me into his house and shoot a documentary about him."

Born in 1945, Leda Papaconstantinou grew up in Larissa, Salamina and Athens, and studied in Athens and the UK. In 1967, while she was abroad, a coup d'état took place in Greece and a dictatorship was enforced. Nevertheless, Leda Papaconstantinou and her husband, artist David Hughes, decided to move to Greece in 1968 and join Papaconstantinou's parents on the island of Spetses — where they had moved the year before and were working as craftspeople. Leda Papaconstantinou and David Hughes also began making applied art objects for a living, and soon opened their own art shop. "We were also collaborating with other Greek artists," she recalls, "ceramicists, jewellery makers... It was a time when Greek arts and crafts were blooming, they had a very serious reputation abroad and were well-designed. That's also how I met Lizzie, who walked into my shop one day and simply introduced herself."

Lizzie Calligas also has a close relationship to Spetses. She was born in 1943 in Athens, but she spent all her summers on the island, where her grandfather had bought a house in the 1930's. "My grandfather was a painter and my mother was a painter too, Nelly Kyriakou-Calligas. I never met my grandfather, because he died a year before I was born. I just know him through his works. His presence is very strong in our house, much of the furniture is painted by him. My mother painted a lot though, so I grew up in a home filled with painting. I married very young and had children very young, and wasn't planning to study art or something like that. But when I got my divorce in 1973 I decided to enrol to the Athens School of Fine Arts. I was 32, with three children."

Lizzie Calligas's family house is right on the seafront and next to the monastery of Agios Nikolaos. We can actually see it while we're doing our interview. It has a large terrace about eight meters above the street, and overlooks the sea. It is from this house that her well-known Swimmers series was created, as well as other bodies of work inspired by the island. She continues her narration: "My 'new life through art' so to speak started giving works that are Spetsiot in character. Many of my works, including most of the copper engravings I did back then, are all after Spetses. Even today, a large part of my work has to do with the island. Spetses for me is home."

Lizzie Calligas and Leda Papaconstantinou's work is so deeply embedded in the past and present life of Spetses that their work is an embodiment of their life on the island. On the one hand, Lizzie Calligas creates snapshots of her island life, usually discreet, private, withdrawn. Her photographic work, apart from the swimmers she so dedicatedly documents from her house, also includes plants and found objects. Her work seems to emerge from a personal process of collecting and documenting the minutia of life like a naturalist; it is an ongoing process of archiving the abstract flow of materials and images, or rather, finding the emotional concreteness in the random collateral she collects and depicts.

On the other hand, Leda Papaconstantinou's work is much more socially engaged and the result of self-initiated interaction. An important proponent of Greek performance art in the 1970's and 80's, Leda Papaconstantinou also founded a theatre group on Spetses in 1975 that involved foreign artists and local amateurs. Her performance work has always engaged with social and political commentary with raw, provocative actions and often happened within entire environments she constructed. Her visual work, which includes sculpture, installation and objects of various sizes, tends to be much more tender and subtle — a delicate juxtaposition and weaving of materials that touch upon the most sensitive aspects of human life, executed in balance and respect. As already mentioned above, Leda Papaconstantinou has also been performing field research in Spetses, conducting interviews and producing documentaries about the people of the island.

Doors and windows

For the first time in their long career, Lizzie Calligas and Leda Papaconstantinou are exhibiting together at a double show, 'Two Doors - Two Windows', at the Spetses Ecclesiastical Museum. The exhibition includes works from the past twenty years, with several of them created specially during the Covid-19 lockdown (in Greece this lasted from March to May 2020).

The complementary relationship between the work of Lizzie Calligas and Leda Papaconstantinou — the passive, contemplative on the one hand and the active, public-minded on the other — is highlighted in the exhibition catalogue by art historian Denys Zacharopoulos. A personal friend of both artists, he also came up with the exhibition title, which literally constitutes a description of the exhibition space's architectural features. In the catalogue text, Denys Zacharopoulos draws from Aristotelian theory and the distinction between "theoretical" and "practical" life on one's "journey towards happiness and virtue." Theoretical life, as described in the text, "is based on the way one looks at the world from a critical distance", whereas practical life "is based on the act that leads us through motion and action to touch upon the virtues and passions of the world."

For Denys Zacharopoulos, a door corresponds to action, as one uses it to exit into the world, to engage with it. Conversely, a window is an aperture of contemplation and observation. This has led to certain curatorial decisions in the space, where Leda Papaconstantinou's work is installed between the two doors, and Lizzie Calligas's hangs between and beneath the two windows. The space is thus divided in two, with the artists occupying their own areas and without their works mixing.

The exhibition is based on the dialogue the two artists have been having as colleagues and friends for many years. Due to the lockdown, Lizzie Calligas had to work with only whatever she had on Spetses: "A very large part of my work is in my studio in Athens," she explains. "And since I couldn't go to Athens to bring things, I decided to show what I had here. Most [of the works at the exhibition] are normally hanging in my house!"

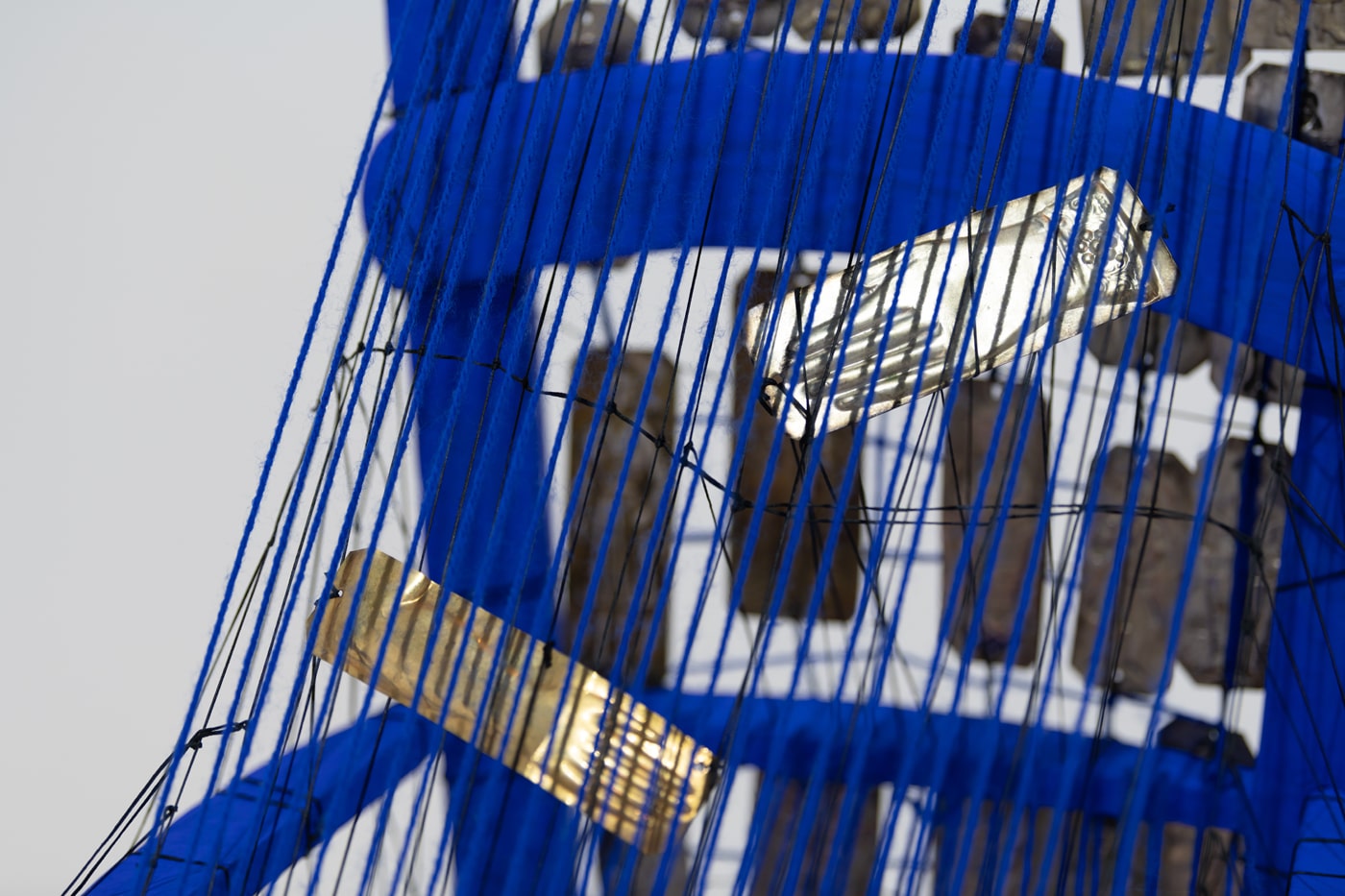

A cobalt blue chair sculpture by Leda Papaconstantinou became the axis around which the entire exhibition developed. The artist used an old wooden chair from her father's workshop, which she painted and wove with blue and black yarn. Several traditional Greek votives known as tamata are incorporated in the work. "I knew about the blue chair," says Lizzie Calligas, "and we've had discussions about using the colour blue. I also happen to have a series of blue works made with an indigo pigment I bought in an Armenian village once. So we were in a dialogue of colour as well. Overall I think we entered a state of balance between us. We tried to strike a balance between the works we had, our friendship, the way we are now, in order to make something that is in equilibrium. That's what this exhibition is about for me."

"There was also mutual trust," Leda Papaconstantinou adds. "She hadn't seen the works I was making, nor had I seen what she was preparing. But of course when you know the other person, you find a way. [With this exhibition] we wanted to give a key for reading not only our work but also this place."

Archiving, mourning, bonding, healing

Working on their exhibition was also a way for the two artists to deal with the effects of the Covid-19 lockdown. Them working together for their exhibition gave them a thing to look forward to, a source of hope. "[The lockdown] has been a difficult period," says Leda Papaconstantinou. "Regardless of how much the place you're in helps — and this is one beautiful place — the coronavirus events have affected us terribly." Since the two friends could not meet from up close, Leda Papaconstantinou would stand under Lizzie Calligas's balcony to chat. "One thing that we have in common with Lizzie is our discipline at work. We are both very disciplined, very productive. It helped me a lot to know that we had a common goal. That the thing we were working on would find its completion in an exhibition at some point."

Lizzie Calligas nods affirmatively. "It's also about survival," she adds. "For me, all this mourning I feel, which characterises these times, there was one way I could banish it. I had to work. I was working for six, eight hours every day, because it was the only way I could banish this demon. Watching the news from the USA, from Britain, worrying about my child who got infected with the virus, my other son who lives in a state with a high number of deaths, not being able to see my grandchildren... All this has a psychological cost. And the only way I could live with this was to keep working. I managed to read a single book during the lockdown, which is a collection of dreams from Franz Kafka's notebooks and diaries. I bonded with that book. It has helped me a lot."

During the lockdown, Lizzie Calligas was incessantly making images of flowers in pots and vases. This resulted in a new body of work, the Dark Flowers, with over forty images (both photographs and paintings) that express her feeling of mourning during the lockdown in Greece. One of the watercolours from this series is included in 'Two Doors - Two Windows'.

The exhibition's only video work is a new documentary by Leda Papaconstantinou. It's the continuation and final part of her work The Box (1981), which consisted of an installation-performance presented at Galerie 3 in Athens. The subject of the work is the former thread factory in Spetses, which lay abandoned for years and was later transformed into a hotel. The video presents interviews with women who used to work at the factory and their experiences there. "With this documentary, this work with the working women, a cycle closes and a new one begins," Leda Papaconstantinou explains. "A new cycle of acknowledgement. I received a message today from the daughter of one of the ladies who are participating in the documentary. She apologised because she won't be able to come see the work, since she's working. So I sent her the link to watch online. I keep sending it to as many people as I can, because the way for someone to learn something is to feel that it is their own."

"Spetses has a history," she continues, "which is gradually becoming archived. And people will acknowledge what the locals have said and done, will acknowledge what is part of their history. For example, there has been performance art on Spetses, but without any fanfare or calling it that. It just happened." Lizzie Calligas adds: "The island has hosted many people of the intelligentsia, who were active in art, music, literature. Important painters like Mario Prassinos for example used to spend their summers here. [Painter and puppeteer] Eleni Theochari-Peraki and [sculptor] Natalia Mela had houses here. Nicolas Calas used to come here too, and Iannis Xenakis went to board school here, at the Anargyrios School. It would be a good thing for the island to realise that [its culture] is not just the regattas and the yachts and the fireworks and all that. We have had people of the avant garde who have left important work behind them [here]. And we should start learning this, to understand this."

History however has not been kind to Spetses, at least not any kinder than the rest of Greece in the 20th century. "Up to now the island's main concern was to not speak of its history," remarks Leda Papaconstantinou. "The civil war ravaged all families here. So they decided to not remember anything. It's true! I know this because I've conducted many interviews with locals."

The Greek Civil War (1943-49) was the first chapter of the Cold War in Europe and was fought between right-wing factions supported by the USA and Britain, and communist factions supported by the USSR. Even before the Germans left the country there were killings reported amongst the two factions, as well as a culling of communists by the Germans. In June 1944 there was such an event in Spetses: communists were fleeing from the Germans on the mainland and got trapped on the island. The Germans found most of them with the help of local anti-communists. Many were brutally tortured and at least thirteen people were killed. Some were hung at the port of Dapia, other were shot on the square in front of Posidonio Hotel, and some were lynched by the mob.

"The executions that took place here — as they did everywhere else [in Greece] — and the way they happened were extremely traumatic," confirms Leda Papaconstantinou. "This is a very small place. A very closed society. And one way for a closed society to cope with trauma is to forget. To bury [its history]. This is why I gave the title Closed Society to one of my works at the exhibition." The work in question is no other than the blue chair entangled with yarn. A familiar, domestic object that acquires a religious, cathartic property as it is plated with metal votives — the latter traditionally placed by the devout on the icons of saints in churches with the request that their prayers be heard. Usually the votives depict the object of the prayer, the recipient of divine intervention. In Leda Papaconstantinou's Closed Society, this tangled blue altar shimmers with images of young men and women, little houses, hands and feet.

Suddenly, the "key for reading their work and this place" becomes apparent. In Lizzie Calligas's salvaged mosaic floor fragment (Mosaics - finds, 2003) and pottery assemblages (Finds, 2020), her miniature sculptures made of broken glass (Flowers, 2020), the oblique corners of her house's ceiling in the morning light (Ceiling, 2006) — in all these works we observe a silent resilience that is putting back the pieces and attempts to make the best of what it has. In Leda Papaconstantinou's icons covered in tar (Hornets, 2020), her lightbox of her hands holding a blue heart (Light box, 1999) and her two organic-shaped sculptures on low plinths (Human Drop and Tree Drop, both 2020) shed an empathetic light on a history that hurts, and imply the ability to cope amidst painful times.

"Τhe locals are all on Facebook already and follow our [museum] page," Leda Papaconstantinou says. "One of the missions of this museum is to build an audience: our goal is for our visitor numbers to increase every year, and to include people from all social classes, visitors and residents alike. Another mission is to educate people, which is something I have been engaged with since the 1970's. All this I would say are done with a system. One makes new work following a system. I believe it's worth doing this. And not for me."

It is already dusk and a group of visitors approaches the exhibition entrance. The two artists welcome them and ask them to wear their face masks and enter in groups of four. As daylight fades, the tightly-set pebble floor of the courtyard seems almost fluid like the sea.

The exhibition Two Doors - Two Windows continues at the Spetses Ecclesiastical Museum through the 14th of September.