Thessaloniki Queer Arts Festival is an annual independent event that was founded in 2017 with the mission to challenge misconceptions and prejudice against queer and LGBT+ individuals through culture and art. This year's edition takes place between 20-28 June under the title "What is fear?", and explores the different meanings fear has for marginalised and oppressed queer individuals and communities. The festival's focus on showcasing underrepresented LGBTQIA artists, writers and activists shines through the selection of artworks that are part of this year's edition, with around 90 participants from Australia, Brazil, Canada, Cuba, Egypt, Georgia, Guatemala, Iran, Mexico, Paraguay, Poland, Rwanda, Ukraine and other countries.

In the following interview, the festival's curatorial team, consisting of Tomas Diafas, Dominic Sylvia Lauren, Vassia Magoula, Evi Minou, Aristea Rellou, and Magda Vaz, talk to und. about the concept, content and challenges of the festival.

The subject “What is fear?” was prophetic in many ways. What are the artists participating in this year’s TQAF most afraid of?

Tomas Diafas: Following last year’s theme What is Eros?, our exploration naturally led to the investigation of the political dimensions of fear, not only in relation to love, but also in light of the constant fear that the LGBTQIA+ community has historically faced. Our collective subconscious, charged by the history of murder and criminalization against us, as well as the experiences we live through today, constitute a very powerful agent within the community; they keep informing our behaviour. If something like that seems prophetic, it’s because we have been lucky enough to reach people from across the globe since the festival was founded, and we have listened to their stories. This year, What is Fear? showcases our personal worries and the anxieties of people from very different backgrounds. The artists participating in the exhibition and the short film festival reached out to us through our open call, and come from diverse backgrounds; some live and work in areas where queerness is a criminal offense, while others live in “safer” environments that presumably grant them additional protection. Together, they speak about the decay of the body and the fear that death will arrive before freedom does. Nevertheless, this festival is not a diary of sorrow, but a manifesto of the superpower that we derive from artivism.

From a curatorial perspective, where did this exploration of fear take you? Have you discovered new areas or ways of seeing/doing? What emerging artistic practices are related to this?

Vassia Magoula: We were excited to see that a great number of artists responded to this year’s topic of fear. In the midst of the pandemic outbreak this theme came as an urgent issue to be explored. Fear determines a turbulence intrinsically related to the soul, the psyche and the emotion, which resides in all of us. Apart from the existential aspect as an emotional state of great intensity and anguish, we could not overlook the social, political and cultural dimensions that the artworks themselves revealed around these phenomena. The material itself led us to a wider discourse of overlapping issues which derived from this theme: violence over bodies, power and state, identity, trauma, memory, discrimination, exclusion, body dysphoria, marginalized bodies, oppression, queer death, post-human visions.

All these above are reflections of our living in a culture of fear. From the very beginning of our lives we are exposed and gradually immersed in this culture, which turns out to saturate our everyday life experience. Homophobia, violence, sexism and oppression are correlated to viruses, which infect society and reinforce distorted imageries. Art, as a site of resistance, had always provoked radical ways to bring compelling things to the forefront, shedding light onto undermined issues. We recognized these variable artistic voices and the necessity to incorporate this diversity as an essential substance of the concept of the exhibition in our exploration of the theme of fear. Bridging the gaps amongst artists, we aimed to create a safe environment in the form of an art platform, where dialogue and discourse are encouraged, as well as the LGBTQI+ community itself.

Our material turned out to be diverse, in terms of medium, style, approach, story-telling, techniques. This sort of multiplicity we wanted to maintain, as we considered it provides ground for people and subjects to narrate their stories as they were originally experienced and perceived. Participating artists have been creative enough to experiment with various media and forms, such as painting, performance, digital art, video, film, GIFs, photography, visual poetry and mixed media practices, bringing new light onto the main topic of this year’s festival. The variety of methods and approaches reaffirms the integral complexity of fear and its potency when articulated in one common language. Instead, we sought out multiple languages and conversations, anticipating that their entanglement may inform a deeper understanding of fear, as well as a thought-provoking conversation with the audience. Be it depictive, performative, visualized, narrative or confessional, any of these approaches reaffirm a reciprocal relationship between artistic practice and progressive healing. The fear theme here works as a lens, through which we can reflect on our fragility, subjectivity and sense of identity, as well as on society’s internal pathology. Through this view, we simultaneously aim for a political stance of resistance against normative identity and oppression.

In your statement you mention that “being queer encapsulates the potential of a liberatory relationship with time, space and society”. What examples are there in this year’s programme that reflect this potential?

Aristea Rellou: The reevaluation of hegemonic histories leads to reinvention through the critical analysis of the two main pillars through which humans experience the world: time and space. Though postmodern vocabularies for the description of normativity are more extensive than those that describe queerness, trajectories that defy temporal linearity and spacial orientation are common among queer people.

The intersectional unpacking of the elements that constitute “queer time and space” inevitably leads to a decolonization of sorts, which calls for the critique of the normative societal structures. From early-childhood experiences to dating, to questions of identity and the legal implications of queerness, from the personal to the political, queer experience commonly begins where normative periphery ends.

In TQAF 2020 x What is Fear? we examine the chronopolitics and geopolitics of queerness, especially in relation to fear. Queerness is understood as a kinder alternative, a break from the capitalist demand for linear, constant progression. In Nat Portnoy’s video work 42 Days (2020), for example, the artist confronts the reality of her father’s terminal disease and deals with grief, abuse and self-harm over the course of 42 days. These 42 days act as a microcosm of the larger currents that pass through the artist’s life, while she waits for the results of the test that will determine if she carries that same disease within her. The narrative coherence of time is also challenged in Matthew Baren’s Redux (2012), a film that invites viewers to consider death as experienced peripherally by the living. The project overlays nine distinct narratives with a non-deliberate synchronisation, in keeping with the premise of the surrealist game, exquisite corpse. Each frame exists in isolation, each character isolated by their experience in a society which chooses not to speak about dying. In the queer renderings of time and geography that are included in the exhibition, such as Estefania Arriaza’s and Fran Ansala’s Sincronismo (2020), the artists present an anthropological, poetic exploration of creativity; one that defies distance (in this case, between Guatemala and Argentina) and the constraints imposed by the recent pandemic, and redefines connection.

These are just a few examples of the proposals included in What is Fear?, that question the linearity of time and space and challenge the confinements that the latter impose. The works in the exhibition actively disrupt the erasure of queer bodies from public space and history and reaffirm their presence, despite of and in light of fear.

The festival’s exhibition is organised into five “rooms” or themes. Can you give us a quick walkthrough of these different areas?

Vassia Magoula: Curating in virtual space was challenging, since we found ourselves on a constant questioning, revisioning, and rethinking of the methodologies and tools of the conventional curation in physical space. Virtual demanded a totally different thinking in terms of presentation and desirable experience. Our attempt was to emphasize the diversity amongst the artworks, as well as to bring them in close proximity. Τhe exhibition is built upon five conceptual lines, each of them reflects on crucial issues around queerness and visibility. To outline this idea, the main topics that emerged by the artworks touch issues of public presence, power, body, memory, and death. We felt quite free to explore and play with the limits of the language and its meanings, as well as the wide possibilities that this arbitrariness allowed us to approach. In an attempt to queer the language, curation turned out to be a playful, anarchist act, aligned with irrationality, unpredictability and linguistic intervention.

This paradoxical approach is summarized in the titles of each “room”. So, in the first room entitled “Conqueering the public” we reflect on queer visibility, exploring notions such safe environment, alternative architecture and public sphere. The artworks here come as alternative structures and modes of establishing queerness in the public space. Room two, entitled “Reli(e)ving the (E)state” is a meditation on the power imposed by the state, through an index of artworks which operate as counter-narratives. The notion of (e)state encompasses an emergent site of resistance against normativity and preconceptions. Room two, entitled “Retrieving the fleshed”, is devoted to the body and the practices, meanings, memories and experiences which inform subjects’ authority on their own bodies and subjectivities. Room 4, entitled “Reciting the(ir) reflection”, revolves around the stories which are underrepresented or systematically degraded by the hegemonic history and the transformative power of reflection. “Unpacking the aftermath” — the final room — acts as a metaphor for death which is explored through the sociopolitical approach of finality, disappearance and post-human visions.

These distinct, yet loosely intersecting areas, are organized so that they unfold as a series of overlapping conversations.

You began working on an online festival well before the coronavirus lockdowns. What sorts of new possibilities did that open up for you and what was the biggest obstacle in organising an online art festival?

Aristea Rellou: After What is Fear? was decided as the question TQAF 2020 would seek to unpack, we immediately went into problem resolution mode. As a grassroots group, made up of individuals spread out all over Greece and Europe, we did not have a base that we all shared. The lack of funding and resources added pressure unto the team and threatened the viability and survival of the festival. Within this context, the idea of hosting this year’s iteration of TQAF online provided a promising alternative to organising an exhibition in a physical space.

The virtual sphere not only allowed our team to work together despite time differences and spatial limitations, but also challenged us to rethink what it means to remove the element of the traditional physicality and aura of an exhibition space from the experience. We therefore started to consider both the possibilities that were opening up to us, as well as the limitations that we discovered went hand in hand with hosting a virtual exhibition.

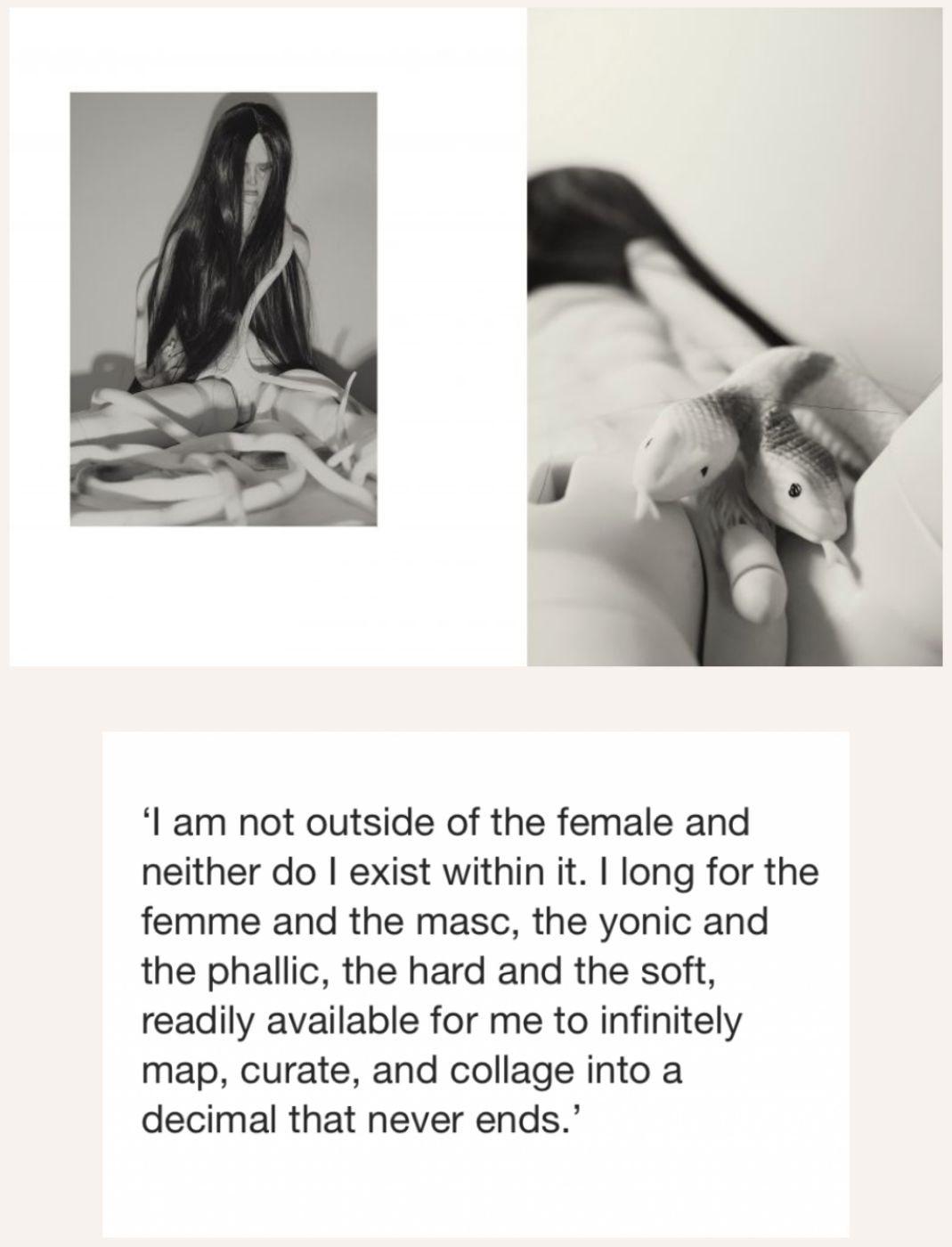

Through our open call, we received approximately 400 submissions, many of which were robust and interesting proposals that investigated the question of fear in a moving and interesting way. Nevertheless, the curatorial position soon became one of translation: we were called to sort through the submitted works and decide which ones translated better to the virtual space that was available to us. The nature of the medium of photography or video, for example, lends itself better to adaptation, but we were lucky enough to also receive proposals that were designed specifically for online presentation. Li Yilei’s digital zine, Venus Im Pelz (2020), for example, presents the images and minimalist poetry created by the artist in the form of an abstract, abridged essay of their ongoing research into the state of gender dysphoria. Other pieces, such as KS Brewer’s animatronic sculpture Baubo (2019), and other installation-based works present additional challenges, so in those cases we made an effort to portray or recreate additional elements of the works in order to enrich the virtual experience of them.

Despite the challenges we came across regarding the presentation of works that could not easily be adapted for online viewing, the fact that we planned for the festival to be online before the coronavirus lockdown came about and forced all of us into digital adaptation allowed adequate time for us to conduct research and think about ways to optimize the potential of our new platform. By using the possibilities presented by the use of the TQAF website and social media, we were able to reach a much wider and inclusive audience, making the most not only of our own local networks but also of the regional connections brought to us through our participating artists. Hosting an exhibition and a short film festival of this scale would incur costs and require resources that are not available to us at the grassroots level. Thanks to this year’s platform we have had the opportunity to create an international anthology of queer fear, reaching marginalized communities and audiences that we wouldn’t have been able to otherwise. Necessity is the mother of invention after all, and inventing we did.

TQAF takes place during Pride Month, but also during major civil and anti-racist uprisings in the USA and beyond. What is the place of queer arts within this unfolding discussion on race and rights?

Dominic Sylvia Lauren: Art has the power to unpack, unveil, tease out, contradict and dismantle dominant discourses. The artistic medium is a platform for discussion, debate, and activism. Queer art, in particular, was born out of political and civil rights movements, and it is largely indebted to the black community. Anti-racist ideals are at the heart of how we operate, encourage and promote queer artists through our platform as a festival, with ‘artivism’ being the incentive for many of the conversations, initiatives and collaborations TQAF takes part in.

Queer and racial politics have always intertwined; we are all fighting to shift power structures and dismantle discriminatory regimes. Now more than ever, queer, race and civil rights intersect and occupy the public space in an effort to be visibile, vocal, and to put an end to the relentless subjugation and criminalisation of minorities. The decision to address ‘what is fear?’ as this year’s theme swiftly and inevitably charged TQAF 2020 with a politicised force, as many of the TQAF featured artists heavily criticise and unpack hegemonic colonial and patriarchal discourses.

The constraint of time, the pressures of capitalism, and the imbalance that is found in an overbearing system of ‘normal,’ ‘straight,’ ‘white’ linearity, strains queer survival, but the presence of queer arts festivals, such as TQAF defy silencing and reaffirm our power. TQAF 2020 features artists and collectives like Louise Mutabazi, Santanu Dutta, Tracing A City, Arvin Ombika, and Jorge Bascuñán who shed light on treacherous colonial histories in India, Mauritius, Brazil and Rwanda and how colonial powers and white supremacy have imposed laws that criminalise, illegitimise, and marginalise queer subjects. By explicating this push and pull between power relations, queer experience and white / Western ideals, these artists emphasise the intersectional nature of queer and racial politics. Documenting the experience of existing in a world where ‘othered’ bodies are silenced, chased, and dismantled, “movement helps us avoid unsafe situations … [and] we have to create ever-evolving strategies for survival,” as artist Louise Mutabazi writes. These ever-evolving strategies for survival are what we are experiencing and witnessing every day on the streets; through these, we are able to unlearn, learn anew and rewrite history.

Tell me more about Thessaloniki as your geographical base for the festival. How does this work now, when the festival is global and takes place mostly online?

Dominic Sylvia Lauren: Thessaloniki serves as a starting point and a central axis for many TQAF projects and collaborations. As TQAF was founded in Thessaloniki in 2017, the previous two editions, What is Queer? (2018) and What is Eros? (2019) naturally unfolded in several venues across the city. We have collaborated with and co-hosted performances, talks and workshops at MOMus - Experimental Center for the Arts, FIX in Art, Labattoir, Ypsilon, Coo and several other spaces in the past 3 years. Public interventions also sprawled across Thessaloniki in an effort to bring queer arts to every corner of the city. We have maintained close relationships with some of these organisations and cultural spaces and hope to collaborate again in the future.

This year, we have kick-started a new initiative, Balkan Queer Network (BQN) powered by TQAF, in an effort to consolidate and forge a large network of artists, activists, and cultural practitioners from across the Balkan region. Through this network, we aim to connect with and offer the opportunity to underrepresented LBGTQ+ artists, writers and activists from across the Balkans and other selected regions to share their practice, offer creative opportunities and connect with like-minded individuals. Thessaloniki is strategically located between the Balkans, Turkey and the Middle East, regions where LGBTQ+ communities are often marginalised, and as we develop strategies for addressing prejudice and resistance to queer inclusiveness in the Balkan region, BQN will serve as a political, cultural and inspirational link to neighbouring societies.

The engagement this year on the festival’s digital channels has increased threefold since our last edition, not only making the festival more accessible to viewers across the globe but also more resilient, agile and adaptable in the face of threats and pressures imposed by lockdowns and museum / gallery closures. As the festival grows, particularly through its online presence this year, we have managed to secure several collaborations in Athens, Madrid and Berlin whilst we continue to maintain strong ties with Thessaloniki artists and curators, as approximately 40% of our audience is based in the wider Thessaloniki region. We hope to cultivate this network of Thessaloniki, Balkan, and international cultural practitioners to create impactful and lasting partnerships.

Is community the antidote to fear?

Tomas Diafas: In the first instance, I would say that the antidote to fear is finding one’s self outside of the community. The community is a platform that empowers the self; it’s certainly positive, as the more hands we have on deck, the broader our thinking expands and grows and any enemy or fear is defeated. Any antidote, however, demands a lot of work and digging, in order for the queer subject to realize where they belong and what scares them. This way, a more complete self, given the right platform and the help of a fist and a caress, moves forward.

Evi Minou & Magda Vaz: We think that many of the fears that are generated by social problems are being understood as psychological and individual fears, In this case, the community is, in fact, an antidote to fear due to the recognition of the origin of it and the communal healing process. But, far from falling into the romanticization of it. The fact that many of us share collective traumas doesn’t mean that we are able to help each other. A community that heals together has to contemplate the possibility of internalized patterns coming from the education from an oppressive system. Therefore, we believe it is needed to have a conscious and critical eye.

View the TQAF x What is fear? online exhibition and short film festival on queerartsfestival.gr.

Join online the festival's closing performance on Sunday 28 June at 20:00 EEST on TQAF's Facebook page.